The Enigma Of Thomas Hickey's Wife: A Revolutionary War Mystery

The name Thomas Hickey resonates with a somber note in the annals of American history, primarily remembered for his ignominious role in a plot against George Washington during the Revolutionary War. His execution marked a stark moment, serving as a grim warning to those who might betray the nascent nation. Yet, beyond the historical facts of his crime and punishment, a more intimate question often arises, one that delves into the personal life of this controversial figure: Did Thomas Hickey have a wife? This inquiry leads us down a path of historical scarcity, where the personal lives of common soldiers often remain shrouded in the mists of time.

Unraveling the domestic life of Thomas Hickey, particularly the existence and identity of his wife, proves to be a challenging endeavor. Historical records from the late 18th century, especially concerning individuals of Hickey's relatively low social standing, rarely delved into such personal details unless they directly impacted significant events. This article aims to explore what is known about Thomas Hickey, the historical context of marriage and family during the American Revolution, and why the question of his wife remains largely unanswered, shedding light on the broader human stories often lost to history.

Table of Contents

- Who Was Thomas Hickey? A Brief Biography

- The Context of Marriage in the Revolutionary War Era

- Did Thomas Hickey Have a Wife? Unraveling the Historical Record

- The Broader Social Fabric: Wives of Revolutionary Soldiers

- Thomas Hickey's Crime and Its Aftermath: What History Remembers

- Speculation and Historical Interpretation

- Beyond the Record: The Human Element of Thomas Hickey

- Conclusion

Who Was Thomas Hickey? A Brief Biography

Thomas Hickey, an Irish immigrant, is a figure etched into American history not for heroism, but for infamy. His story is inextricably linked to the early days of the American Revolution, specifically to a critical moment when the nascent Continental Army and its commander-in-chief, George Washington, faced a severe internal threat. While details about his early life are scant, it is believed that Hickey had served in the British Army before deserting and subsequently joining the American cause. This background, perhaps, hints at a man whose loyalties were fluid, or whose circumstances forced him into desperate choices.

He enlisted in the Continental Army, becoming a member of Washington's Life Guard, a unit responsible for the personal protection of the commander-in-chief. This position of trust, however, was tragically betrayed. In June 1776, as the British forces prepared to invade New York, a plot was uncovered to assassinate George Washington, blow up the city's powder magazine, and hand over the city to the British. This conspiracy, often referred to as the "Hickey Plot" or the "New York Plot," involved several individuals, including the Loyalist mayor of New York City, David Mathews, and a number of soldiers from Washington's own guard, among them Thomas Hickey.

Hickey was implicated through the testimony of others involved, particularly a man named Michael Lynch, who confessed under interrogation. It was revealed that Hickey had attempted to recruit other soldiers into the plot, offering them money for their participation. His involvement, though perhaps not the mastermind, was significant enough to warrant severe punishment. He was arrested, court-martialed, and found guilty of mutiny and sedition. His sentence was death by hanging.

On June 28, 1776, Thomas Hickey became the first person to be executed by the Continental Army for treason. His hanging was a public spectacle, witnessed by an estimated 20,000 people, including many soldiers from the Continental Army. George Washington himself ensured the execution was carried out publicly to serve as a stark warning against disloyalty and insubordination within the ranks. This event underscored the fragility of the American cause and the extreme measures taken to preserve it.

While his crime and execution are well-documented, the personal life of Thomas Hickey remains largely obscure. Beyond his military service and his act of betrayal, very little is known about his family, his origins, or indeed, if he had a wife or children. This lack of personal detail is not uncommon for individuals of his status in the 18th century, but it leaves a significant void for those attempting to piece together a complete picture of his life.

Thomas Hickey's Biodata

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Name | Thomas Hickey |

| Nationality | Irish (Immigrant to America) |

| Known For | Member of George Washington's Life Guard, involved in the "Hickey Plot" to assassinate Washington and betray New York to the British. |

| Crime | Mutiny and Sedition |

| Sentence | Death by hanging |

| Date of Execution | June 28, 1776 |

| Place of Execution | New York City |

| Historical Significance | First person executed by the Continental Army for treason. |

| Family Status | Undocumented (specifically regarding a wife or children) |

The Context of Marriage in the Revolutionary War Era

To understand the likelihood of Thomas Hickey having a wife, it's essential to consider the social norms and realities of marriage during the American Revolutionary War era. In the late 18th century, marriage was a cornerstone of society, deeply intertwined with economic stability, social standing, and religious beliefs. For most, it was an expected rite of passage, often occurring at a younger age than in contemporary society. Men typically married in their early to mid-twenties, and women in their late teens or early twenties.

Marriage was not merely a romantic union; it was a practical partnership. For men, a wife was crucial for managing a household, raising children, and often contributing to the family's economic well-being through domestic production, farming, or assisting in a trade. For women, marriage offered social legitimacy, economic security (though often precarious), and the opportunity to establish a family. The concept of "single by choice" was far less common and socially acceptable than it is today.

However, the outbreak of war dramatically altered these established patterns. The conflict brought immense disruption to family life. Men left their homes to join the military, often for extended periods, leaving wives and children to fend for themselves. This separation placed immense strain on marital bonds and family structures. While some wives chose to follow their husbands as "camp followers," enduring the harsh realities of military life, many more remained on the home front, facing economic hardship, managing farms or businesses alone, and living with the constant anxiety of their husbands' safety.

For soldiers like Thomas Hickey, who were often poor, landless, or recent immigrants, marriage might have been a distant aspiration or a practical necessity. Economic circumstances often dictated the feasibility of marriage. A man with little property or prospects might find it harder to secure a wife, or his marriage might have been a union with someone of similar humble background. The transient nature of military life also made it challenging to maintain a stable family unit, even if one existed before enlistment.

The importance of family ties for soldiers cannot be overstated. Letters home, though rare for common soldiers, often expressed longing for loved ones. The thought of a wife and children could be a powerful motivator for endurance, but also a source of immense worry and despair. Conversely, the absence of such ties might have made some soldiers more susceptible to temptations or less anchored to the cause, though this is purely speculative in Hickey's case.

Did Thomas Hickey Have a Wife? Unraveling the Historical Record

The central question surrounding Thomas Hickey's personal life—whether he had a wife—remains largely unanswered by the historical record. Despite extensive research into the American Revolutionary War, the lives of common soldiers like Hickey are often documented only through military muster rolls, court-martial proceedings, and perhaps a brief mention in a letter or diary of a superior officer. These records rarely, if ever, delve into the marital status or family details of enlisted men, unless such information was directly relevant to their military service, such as a request for furlough due to family illness or a widow's petition for a pension (which would only come much later).

In the case of Thomas Hickey, the historical focus is almost exclusively on his crime, his trial, and his execution. The narrative surrounding him is dominated by the "Hickey Plot" and its significance as a pivotal moment in securing George Washington's leadership and deterring further treason. His personal life, including the existence of a wife, was simply not deemed relevant to the historical accounts written at the time or by subsequent historians. There is no mention of a wife in the court-martial records, in contemporary newspaper accounts of his execution, or in Washington's own correspondence regarding the plot.

If Thomas Hickey had a wife, she would likely have been a woman of humble means, perhaps an immigrant herself, or a local woman from New York or wherever Hickey had settled prior to enlisting. Her existence would have been largely invisible to the official record-keepers of the time. She would not have been a figure of public interest, nor would her personal tragedy (if she existed) have been recorded for posterity. Unlike prominent figures whose family lives were often part of their public persona, a common soldier's family was a private affair, largely unremarked upon by the broader society or the historical narrative.

Furthermore, Hickey's confession, if he made one beyond acknowledging his guilt, focused on the details of the plot and those involved, not on his personal circumstances. The objective of the authorities was to uncover the extent of the conspiracy and identify other participants, not to document Hickey's domestic arrangements. Therefore, the absence of a mention of a wife is not necessarily proof of her non-existence, but rather a reflection of the priorities and limitations of historical documentation from that period.

Scarcity of Personal Records for Common Soldiers

The challenge of determining if Thomas Hickey had a wife is emblematic of a broader issue in historical research: the scarcity of personal records for common individuals, especially those from lower socio-economic strata, during the 18th century. Unlike today, where birth certificates, marriage licenses, and death records are meticulously maintained, such comprehensive civil registration was not widespread in colonial and early American society. Records were often kept by churches, local magistrates, or family Bibles, and many of these have been lost to time, fire, or neglect.

For a soldier like Hickey, who was likely transient, perhaps moving from Ireland to America and then across different locales as a soldier, the chances of his personal milestones being recorded in a centralized or surviving archive are slim. His focus would have been on survival, work, and military duty, not on creating a paper trail of his domestic life. Unless his wife later applied for a pension as a widow (which would require proof of marriage and service, often difficult to obtain), or was involved in some public legal matter, her existence would likely remain unrecorded.

This historical silence forces us to acknowledge the vast numbers of individuals whose lives, while vital to the fabric of their time, remain largely anonymous to us today. Thomas Hickey's notoriety stems from his crime, not from any detailed understanding of his personal journey or relationships. The question of his wife, therefore, serves as a poignant reminder of the countless untold stories from the past.

The Broader Social Fabric: Wives of Revolutionary Soldiers

While we may not definitively know if Thomas Hickey had a wife, we can gain insight into the potential experiences of such a woman by examining the broader social fabric and the roles of wives during the American Revolution. The war profoundly impacted women, transforming their traditional roles and forcing them to adapt to unprecedented challenges. Whether their husbands marched off to war or stayed home, women became central to maintaining society and supporting the war effort.

Many women, known as "camp followers," chose to accompany their husbands on campaigns. These were not merely passive observers; they performed vital services for the army, including cooking, washing, mending clothes, nursing the sick and wounded, and sometimes even participating in battles. While often viewed disparagingly by male soldiers and later historians, their contributions were essential to the daily functioning and morale of the military. They faced harsh conditions, disease, and the constant threat of violence, yet their presence provided a semblance of domesticity and care in an otherwise brutal environment. If Thomas Hickey had a wife, she might have been one of these resilient women, following him from encampment to encampment.

However, the majority of soldiers' wives remained on the home front. These women took on the full burden of managing households, farms, and businesses in the absence of their husbands. They cultivated crops, raised livestock, handled finances, and cared for children, often with little or no assistance. They faced severe economic hardship as inflation soared, supplies dwindled, and their husbands' military pay was often irregular or insufficient. Many resorted to bartering, seeking charity, or even petitioning local authorities for support. Their resilience and ingenuity were critical to the survival of families and communities during the war.

Beyond the practical challenges, wives endured immense emotional and psychological strain. The constant threat of their husbands' death or injury, the long periods of separation, and the uncertainty of the future weighed heavily upon them. Letters, when they could be sent, were often delayed or lost, leaving families in agonizing suspense. The war, therefore, was not just fought on battlefields but also in the homes and hearts of countless women across the colonies.

The Plight of Families Left Behind

The plight of families left behind by soldiers was often dire. With the primary male breadwinner gone, women and children faced immediate economic vulnerability. Farms lay untended, businesses faltered, and the ability to earn a living was severely hampered. Many families were forced to sell off possessions, rely on neighbors, or seek assistance from local committees of safety or churches, which themselves were often struggling.

The war also brought direct dangers to the home front. British and Loyalist raids, foraging parties, and general lawlessness threatened property and personal safety. Women often had to defend their homes, protect their children, and navigate complex political loyalties within their communities. The lack of reliable news from the front lines meant that rumors and anxieties were rampant, adding to the psychological burden.

For a potential wife of Thomas Hickey, her situation would have been compounded by his ignominious end. If she existed and was known to be his wife, she would have faced not only the loss of her husband but also the social stigma associated with his crime of treason. This would have made her life immeasurably harder, potentially leading to ostracization, further economic hardship, and a lasting stain on her family's name. Such a scenario would likely have driven her further into obscurity, making any historical trace even harder to find.

Thomas Hickey's Crime and Its Aftermath: What History Remembers

While the personal details of Thomas Hickey's life, including the question of his wife, remain elusive, his crime and its aftermath are firmly entrenched in the historical record. The "Hickey Plot" was a serious threat to the American cause at a critical juncture. New York City was a vital strategic location, and its betrayal would have been a devastating blow to the Continental Army's morale and capabilities. The plot involved not just common soldiers but also figures of some prominence, suggesting a deeper network of Loyalist sympathizers and British agents.

The discovery of the plot, reportedly through the confession of a co-conspirator, led to a swift and decisive response from General Washington. He understood the profound implications of such a conspiracy within his own ranks. Trust was paramount in a fledgling army, and any act of treason had to be met with severe punishment to maintain discipline and deter future betrayals. The court-martial of Thomas Hickey and his co-conspirators was therefore conducted with utmost seriousness and speed.

Hickey was found guilty of mutiny and sedition, charges that carried the death penalty. His execution was not just a punishment for his individual crime but a powerful political statement. Washington orchestrated it as a public spectacle, designed to send an unmistakable message to every soldier in the Continental Army. The sheer number of witnesses—thousands of soldiers and civilians—underscored the gravity of the event and the absolute authority of the Continental Congress and its military leadership.

The execution of Thomas Hickey served several purposes: it eliminated a conspirator, deterred future acts of treason, solidified Washington's authority, and demonstrated the fledgling nation's resolve to protect itself from internal enemies. It became a cautionary tale, a stark reminder of the consequences of disloyalty during a time of immense national peril. This historical significance, rather than any interest in his personal life, is what ensured Hickey's place in history books.

The Trial and Execution: A Public Spectacle

The trial of Thomas Hickey was conducted by a general court-martial, a military judicial body. While the specifics of his defense are not widely detailed, the evidence against him, particularly the testimony of fellow conspirators, was apparently overwhelming. The verdict of guilty for mutiny and sedition was swift, leading directly to the death sentence.

The execution itself was a meticulously planned public event. On June 28, 1776, Hickey was led to a gallows erected in a field near what is now Grand Central Station in New York City. Accounts describe a vast crowd gathered to witness the hanging, including the entire Continental Army garrisoned in New York. George Washington himself was present, emphasizing the importance of the moment. The public nature of the execution was crucial; it was meant to instill fear and loyalty, serving as a visceral lesson for anyone contemplating desertion or treason. The impact of this event on the morale and discipline of the Continental Army was immediate and profound, solidifying Washington's control and setting a precedent for military justice in the new nation.

Speculation and Historical Interpretation

Given the absence of direct evidence, any discussion about Thomas Hickey having a wife necessarily enters the realm of speculation and historical interpretation. While we cannot definitively say he did or did not have a wife, we can consider the probabilities and the reasons for this enduring historical silence.

It is certainly plausible that Thomas Hickey, like many men of his time, was married. Marriage was a societal norm, and even men of modest means often established families. He was likely in his twenties or thirties when he joined the army, an age when most men would have been married or considering it. If he was an immigrant, he might have left a wife behind in Ireland, or married after arriving in America. However, without any supporting documentation—such as a will, a family letter, or a record of a wife petitioning for aid or information—it remains pure conjecture.

The historical record's focus on Hickey's crime rather than his personal life is a key factor in this mystery. Historians, particularly those of earlier generations, often prioritized grand narratives of battles, political decisions, and the actions of prominent figures. The personal lives of common soldiers, especially those who committed infamous acts, were rarely considered worthy of detailed documentation. Hickey's story was a cautionary tale, not a human interest piece. His identity was defined by his betrayal, overshadowing any domestic life he might have had.

Furthermore, the very nature of Hickey's crime might have led to any existing family members actively seeking to distance themselves from him. If he had a wife, she might have chosen to remarry, move away, or simply erase any public connection to a man executed for treason, to protect herself and any children from social ostracization and hardship. This self-preservation instinct would further contribute to the disappearance of any personal records.

Why the Lack of Information Persists

The persistent lack of information about Thomas Hickey's wife can be attributed to several factors inherent in historical documentation and societal structures of the 18th century:

- Social Status: Hickey was a common soldier, not a landowner, merchant, or political figure. The lives of ordinary people were simply not recorded with the same meticulousness as those of the elite.

- Transient Lifestyle: As an immigrant and a soldier, Hickey likely moved frequently, making it difficult for any local records of marriage or family to be consistently maintained or preserved.

- Focus of Historical Records: Military records focused on service, discipline, and engagements. Civil records were fragmented. Neither prioritized documenting the marital status of every enlisted man unless it had direct administrative implications.

- The Nature of His Crime: Hickey's infamy stemmed from treason. The historical narrative centered on the plot, the trial, and the execution as a warning. His personal life was irrelevant to this cautionary tale.

- Family Disassociation: If a wife or family existed, they would have had strong incentives to sever ties and remain anonymous to avoid the stigma associated with his execution for treason.

- Loss of Records: Over centuries, countless historical documents have been lost due to fire, natural disaster, neglect, or simply the passage of time.

These factors combine to create a significant void in our understanding of Thomas Hickey's personal life, making the question of his wife a compelling, yet likely unanswerable, historical mystery.

Beyond the Record: The Human Element of Thomas Hickey

While the historical record offers little about Thomas Hickey's personal life, including the elusive question of his wife, it is crucial to remember that he was, despite his infamous actions, a human being. Like all individuals, he would have had a past, hopes, fears, and perhaps personal connections that remain hidden from us. The silence surrounding his private life highlights a broader truth about history: it often focuses on the grand narratives, leaving the intimate stories of ordinary people untold.

The American Revolution was fought not just by generals and statesmen, but by thousands of common men like Thomas Hickey, each with their own complex personal circumstances. Many of these soldiers left behind wives, children, parents, and siblings, enduring immense personal sacrifice. The universal human desire for connection, family, and belonging would have been as strong in the 18th century as it is today, even amidst the chaos of war.

The mystery of Thomas Hickey's wife serves as a poignant reminder of the limitations of historical documentation and the countless individual lives that form the backdrop of major historical events. It encourages us to look beyond the documented facts and consider the broader human experience of the era. Perhaps he was a lonely man, perhaps a husband, perhaps a father. We may never know for certain, but the question itself invites empathy and a deeper appreciation for the rich, often unrecorded, tapestry of human lives that constitute our past.

Conclusion

The inquiry into whether Thomas Hickey had a wife leads us to a fascinating intersection of historical fact and enduring mystery. While Thomas Hickey is firmly etched into American history as the first soldier executed by the Continental Army for treason, the details of his personal life, particularly regarding his marital status, remain largely undocumented. The historical records of the 18th century, especially concerning common individuals, simply did not prioritize such intimate details, focusing instead on military service, legal proceedings, and major political events.

The absence of any mention of a wife in contemporary accounts of his crime, trial, or execution is not conclusive proof of her non-existence. It is more a reflection of the historical priorities and the challenges of documenting the lives of ordinary people during a tumultuous period. If Thomas Hickey did have a wife, her story, like that of countless other women during the Revolutionary War, would likely have been one of resilience in the face of hardship, perhaps compounded by the stigma of her husband's infamous end. The broader context of marriage and family life during the Revolution reveals the immense pressures and transformations experienced by women whose husbands went to war, whether as camp followers or as managers of the home front.

Ultimately, the question of Thomas Hickey's wife serves as a powerful reminder of the untold stories of history. It highlights the vast human experiences that lie beneath

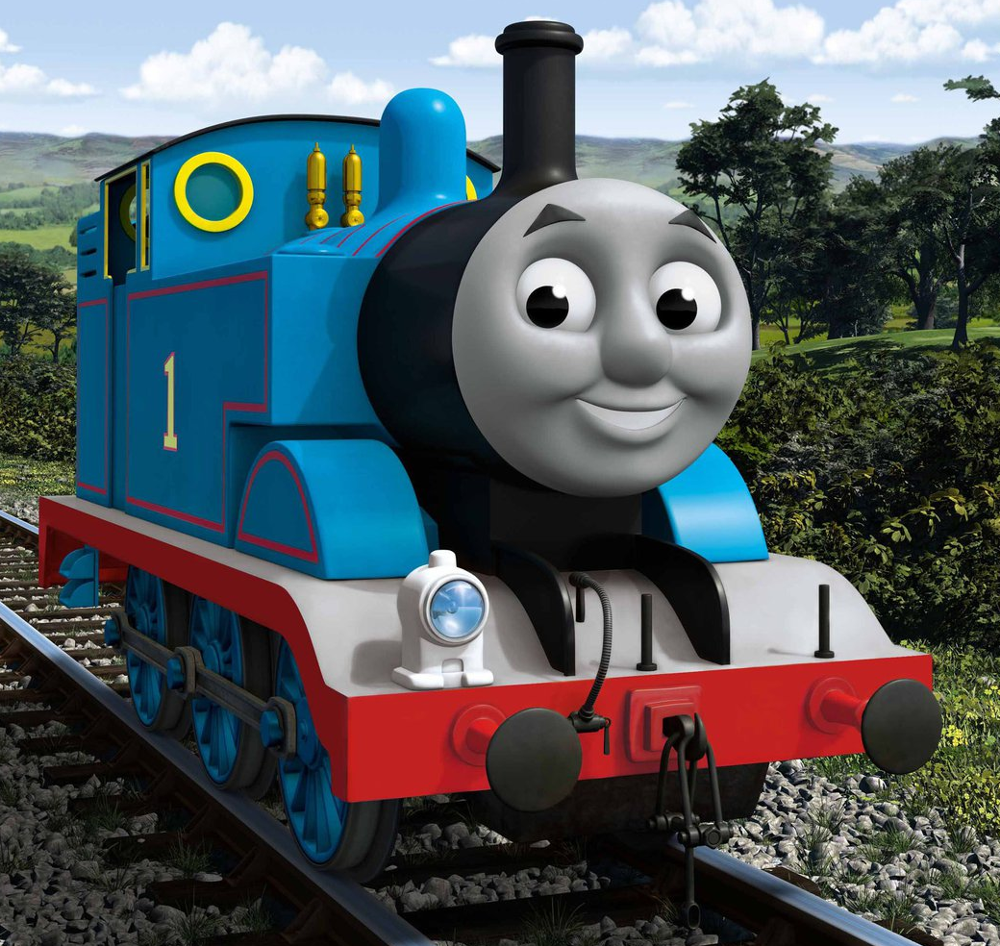

Thomas (Thomas and Friends) - Films, TV Shows and Wildlife Wiki

A Brief History of Thomas the Tank Engine

Discuss Everything About Thomas the Tank Engine Wiki | Fandom